If you ever find yourself in Medellín, Colombia, a word to the wise: there are few better ways to spend an

evening than outdoors, amongst friends old and new, on a sandy pitch in a not-central part of town, drinking

copious amounts of $1 beer and hurling one-and-a-half-pound steel disks at exploding packets of

gunpowder.

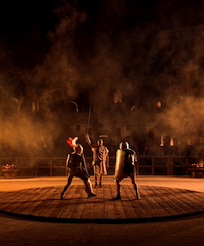

Which is exactly what I’ve had the pleasure of doing, one night a week for the last three weeks, during (somewhat) competitive games of Colombia’s beloved national sport: tejo.

In that time, during incessant swigs from perspiring bottles of Aguilas, I’ve done a lot of thinking—about Colombia, about love, about the best way to toss this frickin’ thing so it makes a little triangular packet of gunpowder, lying on the lip of a small metal ring embedded on a board of clay 20 meters away, explode into a wisp of smoke.

Here are five of those thoughts:

Meditation No. 1: Divulging Information About Your Amateur Tejo League and the Colombian Girl’s Response

Tejo has its origins in the region’s indigenous cultures, but today it shares more DNA with those leisurely diversions pursued in between cold drinks—diversions like pétanque (in France), bags or cornhole (in the Midwest) and bocce ball (in Italy).

While its popularity has certainly risen among all classes, the sport is still oft considered a working-class activity. When I told a Colombian girl I was playing in an informal league, she responded by saying, “I’m imagining you as an old man with a beer belly.”

Which speaks to both the traditional view of tejo and how unlikely I am to get laid.

It is not wise to mix tejo and pleasure.

Meditation No. 2: Toward a More Perfect Drinking Game

What are the elements of a good drinking game? It’s a vital question, and one that we, as a relatively thirsty species, have been asking ourselves since the ancient Greeks invented the Olympics (one presumes).

Some ideas:

—It should hold your attention.

—But it should require very little actual skill, decision making or bodily coordination.

—And the more things involving fire, the better.

A quick primer on tejo: throw a steel disk called—surprise—a tejo and try to hit one of the mechas, which are little bags filled with gunpowder lying around the lip of the small metal ring in the center of the clay bed, and watch it blow up. Basically, it’s cornhole with explosions.

Like other games in the boules family, the rules and regulations of tejo can be pretty lax. In theory, you should play with six people to a team, alternating throws until one team gets 27 points. When I play at Cancha de Tejo, a game venue in Envigado—a quaint town just outside of Medellín city limits—we determine the winner by who has the most points in a set amount of time.

Unlike other games in the boules family, however, it’s almost impossible to grow complacent during a match, because you never know when something might explode.

This makes tejo a close-to-perfect drinking activity.

Meditation No. 3: Loud Noises and Alcohol—A Match Made in the Heaven That Exists Only Inside My Head

Consider these facts: explosions are loud. Alcohol narcotizes the senses.

Therefore: explosions are materially less loud when one consumes between three and six beers.

In conclusion: it is better to play tejo when consuming beer, because one can better enjoy an explosion when noise from said explosion is less (materially) loud. Also: beer tastes nice.

So there you have it: science.

Meditation No. 4: Why Is Tejo Not Popular in America Yet?

Anthony Bourdain played it during an episode of Parts Unknown. We are a sovereign, beer-adoring nation. God knows we have enough gunpowder...

This seems like a no-brainer.

Meditation No. 5: On the Catharsis of Making Things Explode

I went on a walking tour of downtown Medellín the other day, which is not frequently visited by out-of-towners. It can be pretty dicey, at least at night. There is a street our guide called “porn street,” adjacent to an old church, which pretty well lives up to the name. The tour made for an interesting afternoon. And one thing our guide said in particular stuck with me.

We were by the metro station (Medellín is the only city in Colombia with a metro, so it’s a big point of pride for Paisas; it’s also weirdly high on Trip Advisor’s list of things to do here). He told us of the bombings and atrocities conducted during Colombia’s decades-long conflict, including one involving a grenade dropped from the top of the metro’s stairs on the people below. Needless to say, it was a horrible act of terror. And yet our guide ended the anecdote on a hopeful note, praising Colombia’s ability to occlude the darkness, ever creeping into the country’s conscience, and to maintain their infamously jovial disposition.

The everyday notion of “forgetting” he presented has positives and negatives. On the positive side, it has helped lead to the recent resolution for peace with the FARC, the largest of the country’s guerrilla armies, who will now have, amongst other things, real political representation in the Colombian congress. On the negative side, talking about the drug war is still pretty taboo, particularly amongst older generations. According to our guide, the subject is not yet taught in schools.

Given its unique mix of revelry and violence, tejo, to an outsider, can feel like an ample, if not totally coincidental, reflection of the Colombian psyche. There’s something inherently cathartic, too, about hitting one of the mechas: the firecracker blast, the inevitable celebration, the earthy smell of gunpowder billowing from the clay...

It’s really quite beautiful.

And loud. It’s also really quite loud.

Which is exactly what I’ve had the pleasure of doing, one night a week for the last three weeks, during (somewhat) competitive games of Colombia’s beloved national sport: tejo.

In that time, during incessant swigs from perspiring bottles of Aguilas, I’ve done a lot of thinking—about Colombia, about love, about the best way to toss this frickin’ thing so it makes a little triangular packet of gunpowder, lying on the lip of a small metal ring embedded on a board of clay 20 meters away, explode into a wisp of smoke.

Here are five of those thoughts:

Meditation No. 1: Divulging Information About Your Amateur Tejo League and the Colombian Girl’s Response

Tejo has its origins in the region’s indigenous cultures, but today it shares more DNA with those leisurely diversions pursued in between cold drinks—diversions like pétanque (in France), bags or cornhole (in the Midwest) and bocce ball (in Italy).

While its popularity has certainly risen among all classes, the sport is still oft considered a working-class activity. When I told a Colombian girl I was playing in an informal league, she responded by saying, “I’m imagining you as an old man with a beer belly.”

Which speaks to both the traditional view of tejo and how unlikely I am to get laid.

It is not wise to mix tejo and pleasure.

Meditation No. 2: Toward a More Perfect Drinking Game

What are the elements of a good drinking game? It’s a vital question, and one that we, as a relatively thirsty species, have been asking ourselves since the ancient Greeks invented the Olympics (one presumes).

Some ideas:

—It should hold your attention.

—But it should require very little actual skill, decision making or bodily coordination.

—And the more things involving fire, the better.

A quick primer on tejo: throw a steel disk called—surprise—a tejo and try to hit one of the mechas, which are little bags filled with gunpowder lying around the lip of the small metal ring in the center of the clay bed, and watch it blow up. Basically, it’s cornhole with explosions.

Like other games in the boules family, the rules and regulations of tejo can be pretty lax. In theory, you should play with six people to a team, alternating throws until one team gets 27 points. When I play at Cancha de Tejo, a game venue in Envigado—a quaint town just outside of Medellín city limits—we determine the winner by who has the most points in a set amount of time.

Unlike other games in the boules family, however, it’s almost impossible to grow complacent during a match, because you never know when something might explode.

This makes tejo a close-to-perfect drinking activity.

Meditation No. 3: Loud Noises and Alcohol—A Match Made in the Heaven That Exists Only Inside My Head

Consider these facts: explosions are loud. Alcohol narcotizes the senses.

Therefore: explosions are materially less loud when one consumes between three and six beers.

In conclusion: it is better to play tejo when consuming beer, because one can better enjoy an explosion when noise from said explosion is less (materially) loud. Also: beer tastes nice.

So there you have it: science.

Meditation No. 4: Why Is Tejo Not Popular in America Yet?

Anthony Bourdain played it during an episode of Parts Unknown. We are a sovereign, beer-adoring nation. God knows we have enough gunpowder...

This seems like a no-brainer.

Meditation No. 5: On the Catharsis of Making Things Explode

I went on a walking tour of downtown Medellín the other day, which is not frequently visited by out-of-towners. It can be pretty dicey, at least at night. There is a street our guide called “porn street,” adjacent to an old church, which pretty well lives up to the name. The tour made for an interesting afternoon. And one thing our guide said in particular stuck with me.

We were by the metro station (Medellín is the only city in Colombia with a metro, so it’s a big point of pride for Paisas; it’s also weirdly high on Trip Advisor’s list of things to do here). He told us of the bombings and atrocities conducted during Colombia’s decades-long conflict, including one involving a grenade dropped from the top of the metro’s stairs on the people below. Needless to say, it was a horrible act of terror. And yet our guide ended the anecdote on a hopeful note, praising Colombia’s ability to occlude the darkness, ever creeping into the country’s conscience, and to maintain their infamously jovial disposition.

The everyday notion of “forgetting” he presented has positives and negatives. On the positive side, it has helped lead to the recent resolution for peace with the FARC, the largest of the country’s guerrilla armies, who will now have, amongst other things, real political representation in the Colombian congress. On the negative side, talking about the drug war is still pretty taboo, particularly amongst older generations. According to our guide, the subject is not yet taught in schools.

Given its unique mix of revelry and violence, tejo, to an outsider, can feel like an ample, if not totally coincidental, reflection of the Colombian psyche. There’s something inherently cathartic, too, about hitting one of the mechas: the firecracker blast, the inevitable celebration, the earthy smell of gunpowder billowing from the clay...

It’s really quite beautiful.

And loud. It’s also really quite loud.