Alert: This article contains some spoilers.

Here’s a murder weapon you hardly ever see in movies: the hammer. Think about it: how often do you watch someone bludgeon someone else with a hammer (minus Thor)? There’s no parrying a hammer. There’s no dodging a hammer. There’s no such thing as a hammer-proof vest. Two people don’t have a hammer-fight. No hammer-wielder can aspire to the balletic swipes and stabs of the knife or the sword. No, the hammer is a brutal, blunt, myopic instrument, its singular action being: to nail.

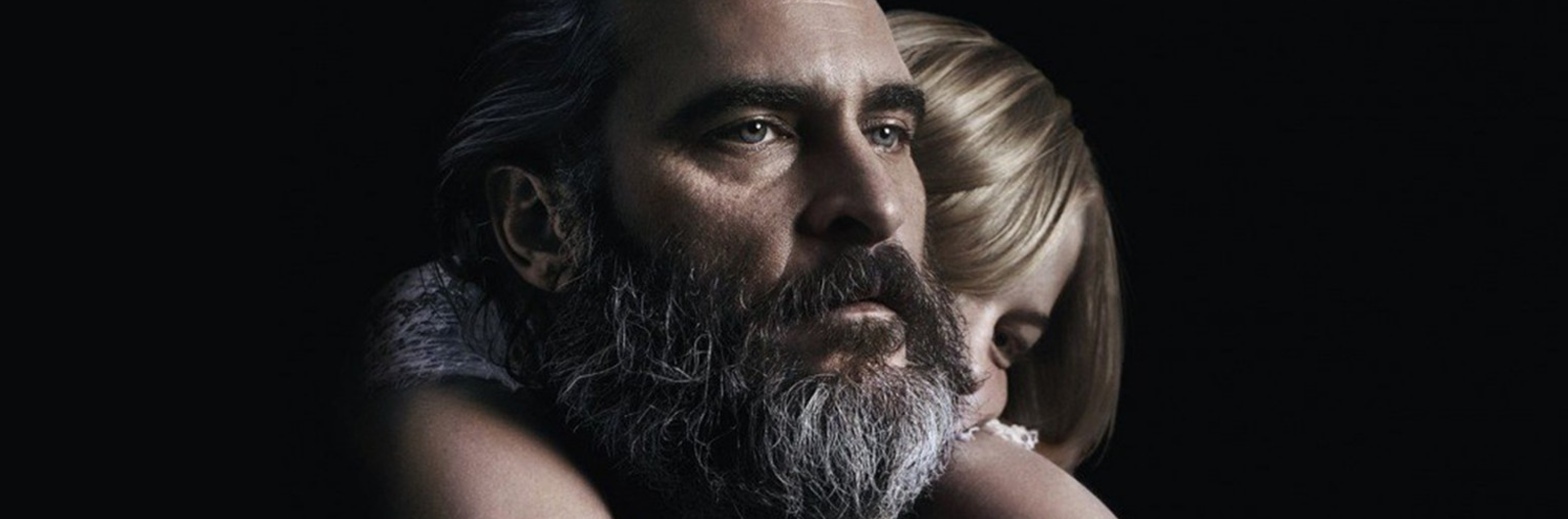

Notable, then, that the lowly hammer is the weapon of choice for Joe, the protagonist of Lynne Ramsay’s tough, yet poignant Cannes Film Festival darling, You Were Never Really Here, based on the novella by the wry bard of the sexually perverse, Jonathan Ames. Rather than a gun or a dagger, Joe, played by Joaquin Phoenix, purchases a hammer from a hardware store before raiding an underage brothel in Manhattan, and beating every man who stands in his path. We see this scene play out from the limited scope of the building’s security cameras, the filter of which removes any residual cinematic gloss. Ultimately, he saves the senator’s young daughter he’d been tasked with rescuing, only to have her fall into the wrong hands once more.

Joe is an army veteran, traumatized both by his experience in action and abuse he experienced as a child at the hand of his father. He lives with his mother, outside of New York City, when he’s not working as a hired gun for a fixer-ish lawyer. His memories come back to him, frequently, in painful, nebulous jolts. The visions of his childhood trauma are especially vague, but Ramsay gives us enough details to imply that it has become the source of his proclivity for hammers and suicidal ideation involving dry cleaning bags. Phoenix, an actor who may use his physicality better than any other working actor, wears the weight of this trauma in his lumbering, uneven gait, and a laboring lilt in his voice. He embodies the spirit of a man who is ceaselessly gasping for air.

What keeps him going, albeit barely, is the renewed search for the senator’s kidnapped daughter, Nina (Ekaterina Samsonov), whose salvation has become inextricable from his own. Apparently, she’s being traded in some kind of clandestine government-sponsored harem for underage girls, and, as a favorite of a fictional Governor Williams, is being kept at his mansion. The government’s desire to keep this whole pedophilic sex trade under wraps—naturally—means many people have to die at the hands of their readily complicit secret service. One such service member falls prey to Joe; in a strangely tender moment, the dying man clasps the murderer’s hand, as they both mumble the words of a familiar tune. It’s an odd gesture, but one that seems to emphasize the fact that we are all children in need of comfort, some leftover scraps of shared humanity. Indeed, Joe’s hammer is a tool for real violence, but its simplicity is also connotative of a fragile juvenility.

You Were Never Really Here feels like a deeply personal film. Yet it’s equally profound in the way it makes the personal political—how it lays the trauma of Joe and Nina, or even that of the slain secret serviceman, at the feet of a cabal of male politicians, channeling in a more twisted, modern version of ancient Greek pederasty (the governor’s mansion is littered with classical art, and what appears to be a Greek sculpture). That Joe is a war veteran makes this connection explicit: his trauma is his trauma but it is also our trauma, made possible by institutions and norms in which we all participate. It’s a feeling all too relevant, in the age of rampant school shootings and a reckoning with sexual assault—horrific personal traumas perpetuated, in part, by the systems in place that have enabled them.

Like a republic willing to hide or dismiss truths about itself in order to survive, Joe too must stifle his painful memories and all-too-frequent thoughts (and attempts) of suicide. The character calls to mind Junot Díaz’s recent essay for The New Yorker, a heartbreakingly profound excavation of his own trauma, which was the result of having been raped as a child. In it, he makes frequent mention of “the mask”—an intangible cover for unspeakable pain.

“Everything I’d been before Rutgers I locked behind an adamantine mask of normalcy,” Díaz writes. “And, let me tell you, once that mask was on no power on earth could have torn it off me. The mask was strong.” Joe wears a mask, too, but it’s slipping.

There’s a sequence near the end of the film, when Joe and Nina sit in a diner. Everything seems, for the time being, relatively okay. She’s been freed; he’s alive. But when she excuses herself to go to the bathroom, Joe takes a gun, holds it up to his mouth and pulls the trigger. Blood splatters across the booths, as his head slumps onto the table. Nonetheless, business proceeds as usual—the patrons carry on their conversations, the background music plays, a waitress walks by and lays the check on the table covered in blood. Nobody seems to notice.

A moment later, Ramsay reveals this as another one of Joe’s ideations. Still, the deception is a powerful one, demonstrating the extent to which Joe lugs around a wound no one else can see.

Except maybe Nina. Perhaps she can see it.

“It’s a beautiful day,” she says.