Chicago’s Happy Place, which runs through August 6th, is located on an unremarkable stretch of North Elston, in the no-man’s-land between Goose Island and River West. Housed inside a nondescript warehouse, I wouldn’t have noticed anything out of the ordinary but for the emoji-yellow windows and the faint tune of an indiscernible pop song wafting out onto the street. Then I walked around the corner to the main entrance and found a growing queue of teenage girls, parents with young children and pairs of Instagram-ready adults waiting to be granted access to the 20,000-square-foot pop-up beyond the cushioned double doors, whose union formed a wry smile.

Happy Place is the brainchild of Jared Paul, a live entertainment producer who’s put on tours for everyone from Paula Abdul to the cast of Glee. Originating in Los Angeles last November, the pop-up is of a piece with the wonder-inducing experiences offered at the ever-popular Museum of Ice Cream, the Rain Room and the forthcoming wndr museum in Chicago's West Loop. But Paul defines his aims in much starker terms than his competitors: “We’re very open and direct about the fact that Happy Place is a themed immersive experience designed to help you escape for a very short time and immerse yourself in happiness...we wanted it to smell happy and look happy and taste happy and seem happy.”

In this way, the pop-up is both more and less specific, and more and less ambitious, than those projects. It’s also inherently, if unintentionally, political, an outgrowth of the constantly regenerative feed of bad or shocking or downright infuriating news that has come to define the Trump era for so many people. One might see it in the same vein as the recent spate of movies—Paddington 2, the Mister Rogers documentary, Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, and Hearts Beat Loud—that the critic David Ehrlich labelled “nicecore”: films which, in a moment when people are starved for good-natured feels, posit kindness as “a transformative force unto itself.”

“I just wanted to do something that at least for a short period of time could let people escape [the news], and maybe [afterwards] they’ll be a little more equipped to deal with it in a small, minor way,” Paul says, adding, “I don’t kid myself to think that one hour in a 20,000-square-foot building is going to solve any major problem we face in our country and our world.”

I myself was cynical upon entering Happy Place. From what little I’d read, it seemed like a coup for hungry Instagrammers, looking for their next big post. The short introductory film past the double doors did nothing to abate my skepticism; with its jubilant cartoon kid host and its promise of “no sadness, no worries, no tears,” it came off, to me, like a juvenile piece of agitprop—an exorbitantly sanguine parody of itself.

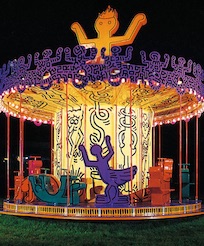

And yet, exploring the various rooms inside the pop-up was a genuinely joyous experience. The first featured a pair of seven-foot tall stilettos made of a million—yes, a million—yellow candies, and an entire wall made up of gumball machines. Another room involved a 20-foot double rainbow and a “pot of happiness,” essentially a ball pit in a giant Leprechaun-esque receptacle. There was an upside down room, designed like a young girl’s bedroom, with furniture hanging from the ceiling. A hallway at the halfway point led through six 11-by-3-foot “cubbies,” from which hung sequins and white chains against a hot pink background. My personal favorite, and one of the most popular installations, was the third and final pair of cubbies, decorated with hundreds of rubber ducks and a yellow bathtub full of plastic yellow balls. I would defy anyone to submerge themselves in it and not leave with a smile on their face.

Some of the more grandiose installations are in the second half of the experience. The world’s largest confetti dome, which is like a life-sized snow globe, contains half a million pieces of confetti. The “Super Bloom” room is dark but filled with 40,000 golden flowers, suspended above the ground. When you enter, you’re meant to climb a little stepladder beneath the flowers and stick your head up through a hole. It’s disarming, a little trippy and virtually impossible not to enjoy.

I’m tempted to call Happy Place a kind of simulacrum of happiness—a manifestation of an anodyne idea of happiness—but in reality the rooms are far too imaginative and idiosyncratic. They felt surprising in the moment even if, upon reflection, they seemed obvious: of course, you might think, making confetti snow angels and eating rainbow grilled cheese is emblematic of the platonic ideal of happiness. But at the same time, it’s not like you would ever think to make that happen.

Naturally, happiness in Happy Place is also contingent on taking photos. Everybody inside was doing it, including me, in every room. It is the experience’s primary activity. The space is equipped with over 400 lights, and the rooms are designed with Instagram in mind—repetition within the installations, as well as their size and scale, are key.

“The number one goal is to make people happy and to wow them and for it to be a spectacle,” Paul says. “And yes, I think a part of that, like, anything, is people taking pictures of what they see, because it’s a huge part of our social environment now.”

In the social media age, that old dictum “Happiness is only real when shared” has never rung truer—particularly if you tack on the phrase “on Instagram.” If you jumped into a ball pit under a double rainbow and didn’t share it on social, did it really happen? An indisputable truth about contemporary society is that we live as much on our screens as we do in the physical world, and if something happens in one place and not the other, it doesn’t feel as real; how could it?

But Happy Place is not the most Instagrammed barn in America. You don’t go there because it’s so widely photographed; you go there because you want to experience it, and the act of Instagramming and experiencing Happy Place just so happen to be inextricable from one another. Which makes it different than visiting the Eiffel Tower just to take pictures, or going to brunch just to Insta a particularly photogenic slice of avocado toast.

“The technology is essential is accentuating and memorializing the experience,” Paul told Forbes last year. “But it’s not taking them out of the experience. They’re not avoiding it. They’re not avoiding communication. They’re actually using the technology to say ‘Jump again! I want to use the technology to actually create a memory!’ I think that’s different than avoiding human interaction. I do enjoy that this genre of entertainment is using technology as a positive part of life. I’m seeing this place evolve in front of my eyes.”

When I left Happy Place and reentered the real world, I felt oddly reset. I was surprised. My idea of a “happy place” would probably be tuna sandwiches on a golf course near a lake with ice cold beer at my disposal. I’m also not a big Instagrammer, and have never particularly enjoyed being photographed. A day later, I admitted as much to Paul on the phone.

“Sure, I’m not much of a selfie taker myself, but I love doing things that are unique and fun and immersive and, most importantly, things I can enjoy with my family,” he said. “It’s such a communal experience, whether you’re going with a group of friends or on a date or with your family. I’m humbled to say I’m yet to talk to someone who didn’t enjoy it.”

All photographs by Barry Brecheisen