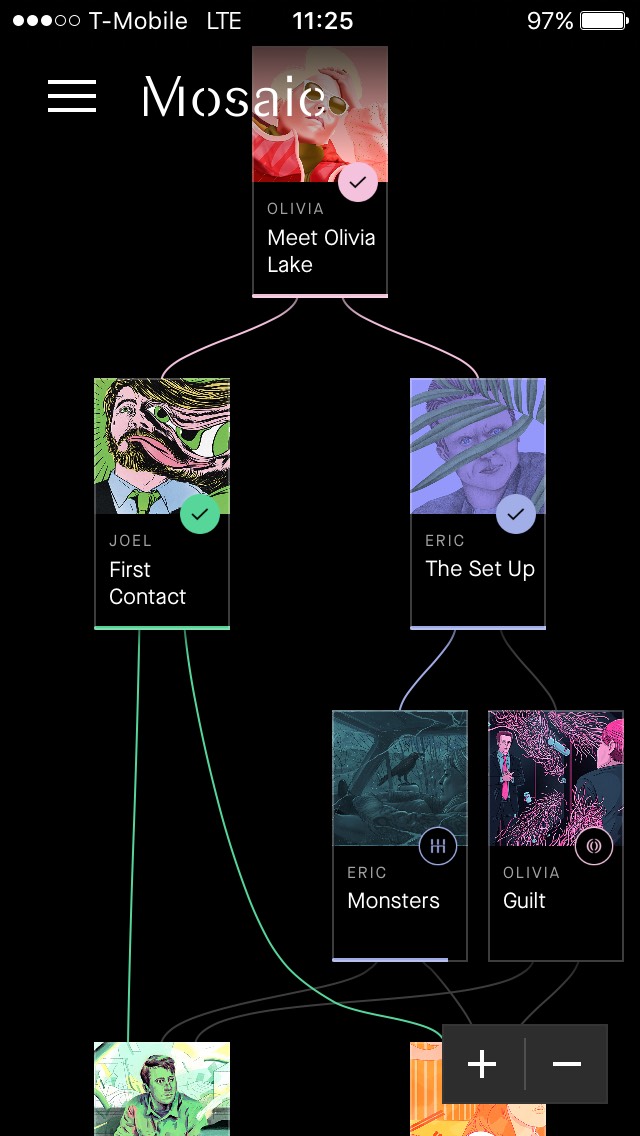

The latest project from restless director Steven Soderbergh (with HBO), Mosaic, centers on the murder of Olivia Lake (Sharon Stone), a world-famous children’s book author, and owns a substantial chunk of land in the quaint yet sophisticated ski town of Summit, Utah. Oozing with sex and fearing her own mortality, she’s taken to hosting “strays” of all kinds—dogs, cats, hot young artists—including the handsome hunk of Midwestern man, Joel (Garrett Hedlund), an aspiring illustrator she “fancies for all of five minutes.” She also meets and falls in love with a grifter, Eric Neill (Fred Weller), who was hired by a wealthy investor to cajole Olivia into parting with her land. Ultimately, he falls in love with her, too—for real. They get married. She expels Joel from her home. And on the night Eric reveals the reason they met in the first place, Olivia Lake goes missing.

Given his checkered past as a con artist and the mounting evidence against him, Eric confesses to the murder and takes a plea deal. Four years later, however, Olivia’s body is found. There is new evidence; the case is reopened. Petra Neill, Eric’s sister, a sharp, beautiful art history geek, decides to launch an investigation herself, hoping to exonerate her brother. Could someone else in this sleepy town have killed Olivia Lake?

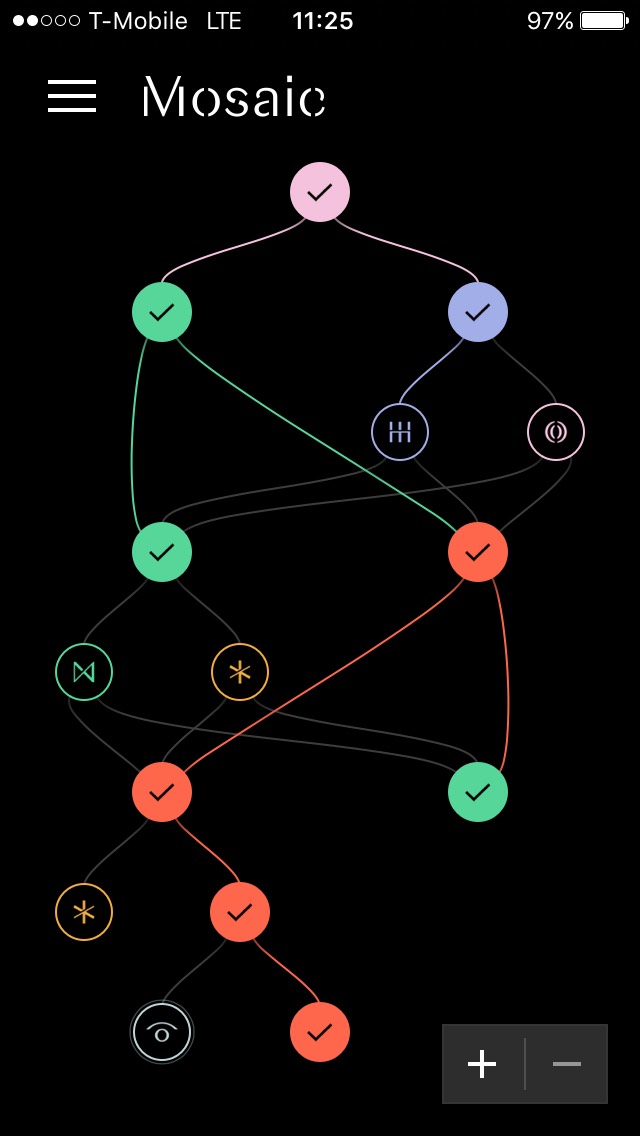

What follows is a relatively straightforward crime procedural, told in a radically complex way. That’s because Mosaic, as of now, exists entirely on an iPhone app, chopped into clips ranging from approximately eight to 38 minutes that are laid out in a sinuous flow chart. Everyone starts at the top of the chart, with a clip entitled “Meet Olivia Lake.” From there, though, you choose which path to follow, and, to an extent, how much of the story you wish to see.

The app's design is sleek and its functionality intuitive, eschewing gimmickry with subtlety. At the end of a clip—which essentially serve as "episodes"—you're merely presented with two screens, each featuring a different character. The purpose here is to get you to follow the arc of the character that interests you most. Theoretically, this is a good concept—there are particular characters in any show that we want to see more than others. In practice, however, this concept feels flawed. Given the structure of the narrative map, you're going to have to watch certain characters' clips, anyway. I chose to follow Joel's arc early on, mostly because I like Garrett Hedlund, and soon found myself in a dead end, which forced me to return to a point in the story I felt I'd already moved past. While the interface encourages you to binge one clip after another—as I did—I would encourage you to consult the "map" after each clip, and consider your moves more carefully. All told, the app contains over seven-and-a-half hours worth of material; to get to the end, you probably only need (or want) to watch a little over half that.

One might be inclined to describe the experience as video game-like. But, as Soderbergh says himself, that’s not quite right. You are not an active actor in the show, after all: this is not a first-person RPG where characters talk to you and, through a limited range of choices, you influence their behavior. The ending is the same, too, no matter what; the only factor that varies from user to user is how you get there. It would be more appropriate, then, to liken your role in Mosaic to that of an editor, choosing what the viewer (you) does and does not see, adding and subtracting, meticulously shaping the story from the surplus of material provided.

This is a shrewd and deliberate choice by Soderbergh, an indefatigably creative artist who is perhaps more cognizant of and amenable to shifts in technology than any other director of his generation (he just shot a horror movie on an iPhone), but also clearly obsessed with the fundamental act of storytelling. In many ways, the work of the viewer here reflects the work of the characters, who are tasked with methodically rewriting the past. Joel, for his part, is forced to reconstruct the night of the murder from an alcohol-driven blackout; Petra, who initially believed her brother guilty of the crime for which he was convicted, finds new evidence that casts the murder in a new light. Even Olivia’s famous book, Whose Woods Are These, contains a lesson about narrative point-of-view: read one way, we’re told, it’s a story about a hunter trying to protect his family from a bear; read the other, it’s a story about a bear trying to protect his cubs from a hunter.

The problem here is that, for a show intent on showing different perspectives (most of the clips are categorized by character), those different perspectives offer very little to the viewer. From my experience with the app, the designers of Mosaic do an admirable job of limiting repetition. They also manage to fill you in on necessary information you may’ve missed by taking one path over another. Every so often, while watching a clip, you’ll unlock “Discoveries,” little push-notifications that alert you to additional information—in the form of news articles, short videos, voicemails, emails and the like—which you can seamlessly watch or view or read before returning to the main clip. And yet, too often the same scenes or plot points told from different perspectives are just that: the same. They by and large fail to provide new information into either the character’s inner life or the story-writ-large.

One of the most interesting pieces of film or TV of the past however many years—and I realize I’m all but alone in this opinion—was the first season of Showtime’s The Affair. That show, too, told the same story—of a steamy extramarital affair—from the point of view of its two (sometimes four) protagonists. The difference between The Affair and Mosaic, though, is that those perspectives fundamentally influenced the narrative: from one character to the next, the same sequence of events felt completely different. There was something both intensely compelling and wildly fun about watching a story unfold that way; it was, in some ways, like a game of emotional spot-the-difference. The Affair seemed like, amongst the other things it tried and failed to be, a meditation on how impressionable the flimsy tree branches of memory are to the wintry gusts of the heart. That show was about the stories we tell ourselves; Mosaic is about the stories we perpetually revise and present to others.

To be fair, Soderbergh admits that Mosaic is a sort of first draft, and hints that, in future projects, he and his co-creators will likely play around with the emotional and attitudinal stuff that might alter perspective. But in its current iteration, Mosaic is a limp story, unremarkable in almost every way but its form (Sharon Stone and Garrett Hedlund do their best to infuse some life into it). If I watched the story I put together for myself straight through, again, I would certainly notice some plot issues. Some characters, like the awkward and unconvincing frenemy cop Nate Henry (Devin Ratray), wouldn’t work in any story, regardless of the medium. And Paul Reubens (aka Pee Wee Herman), who plays Olivia Lake’s gay best friend, feels, at times, like a cast member of a different show. Many of these problems, of course, could have arisen from the way I “edited” the show. I’ll be curious to see how Soderbergh envisioned the story playing out, when Mosaic airs linearly as a limited-series on HBO this January.

In spite of its shortcomings, the app is undoubtedly impressive, if not commercially unviable. It also represents an appealing alternative to the more video game-y aspects of VR, which many are betting will be the entertainment medium of the future. Mosaic is, after all, still very much a television series. I'm not sure we'll be able to say the same of series experienced in virtual reality.

And yet a part of me wonders whether this method of storytelling isn’t five or ten years ahead of its time. An app is a natural home for longform TV these days, and an iPhone a natural platform on which to watch it. But the inherently active nature of Mosaic is somewhat antithetical to the primary mode of media consumption in 2017. Binge-watching is passive. You don’t even have to press play to watch the next episode, much less choose it. Will anyone other than film nerds and Soderbergh diehards bother wasting their precious brainpower editing something as they watch it?

Not with this show, they won’t.