It’s 2017, but the ‘90s are everywhere.

O.J. Simpson, the focus of the penultimate media event of the decade, was the subject of not one but two of last year’s most memorable television programs. ‘90s fashion, particularly streetwear, seems more prevalent than ever. Will and Grace are returning to NBC; meanwhile, on MTV, today’s youth will soon bear witness to the premiere of 90’s House, a competition show “that places 12 millennial housemates in a 90’s inspired house and forces the young adults to officially unplug their modern-day devices.” And, lest we forget, last November's election served in part as a referendum on the Clinton-era culture wars, thrusting a familiar cast of characters, including Matt Drudge, Newt Gingrich and the Clintons themselves, back into the spotlight. Not to mention, one of the decade’s original tabloid stars, who now sits on a gilded throne of baseless tweets in the Oval Office.

It’s quite fitting, then, that today we see the publication of David Friend’s The Naughty Nineties: The Triumph of the American Libido (and, coincidentally, Hillary Clinton’s election memoir, What Happened). A definitive sexual history of the decade, Friend’s book, like sex itself, touches every part of the culture, from science (the advent of Viagra), to technology (the advent of the Internet, and Internet porn), to the arts (i.e. the rise of reality TV), to politics (remember that whole Monica Lewinsky thing?). Through a fascinating mix of cultural criticism, mini-histories of subjects famous and forgotten and anecdotal experiences—in one illuminating chapter, the author attends an Orgasmic Meditation session with his wife—Friend paints a compelling picture of the decade that has come to define what he calls the “Trump Teens.”

As our humble narrator, Friend, a longtime Vanity Fair editor, writes about sex with a delicate balance of sobriety and cheeky wit. Rising to meet the subject at hand, Friend eschews the dry droning-on that may encumber similar texts; he is not averse to the occasional pun or playful turn-of-phrase. On top of everything else, the book, to a clueless millennial such as myself, amounts to a veritable trove of ‘90s cultural marginalia, including a paragraph-length pop culture history of the blowjob, the origin of the booty call, frequent mentions of a truly jaw-dropping Norman Mailer/Madonna Esquire interview, “teledildonics,” a 1997 HBO movie called Breast Men starring David Schwimmer and a welcome reminder of the time Charles Barkley called in to Howard Stern to say he had shared a bathtub with Donald Trump and some “hot babes.” (Uh-huh. Yup.)

Ultimately, in writing a sexual history of the ‘90s, Friend has, both wittingly and not, penned a cautionary tale about our current moment, where the tabloidization of the media and the increasingly redundant line between public and private, fact and fiction, has given way to the reality TV star perched in the White House. Having devoured the book, I spoke with Friend over the phone and email about his writing process, the state of the modern American male and the most overlooked sex symbol of the ‘90s.

Spoiler: It’s not who you think it is.

One thing I couldn’t help but think about while reading this book was that I am, of course, at 25, coming at this book from a millennial’s point of view. This stuff really is history for me in a way that it isn’t for a boomer or Gen-Xer. We have a vague idea of what went down, naturally, but I think few of my friends would know who Paula Jones, or Anita Hill, or Gennifer Flowers, or Lorena Bobbitt were. I’m wondering if that’s something you were thinking about when writing the book.

You’re right to raise this, because in writing a book, people look at things from a real perspective and try to get into the reader's mind, but really you can’t, you have to write to satisfy yourself. And while for reasons of context and clarity you have to think about the reader, in many ways I was just writing a book I thought would appeal to Boomers. But in fact [I realized] as soon as I signed the galleys at the Book Expo in New York...I had a long line and every person in line was a twenty or thirtysomething, because they looked at the book and the '90s as their decade, the decade when they grew up and came of age. So it was really Gen-X’ers and Gen-Ys who, as you say, perceive this period as being foundational in their formation. It’s great to have that broad appeal. Because I think it would appeal as recent history to your generation and as sort of an embarrassing decade for my generation.

I do think of it as my decade, but much more in a cultural way. I think few people my age would think of it as the Clinton years, because we were too young to process it at the time.

Well, we didn’t think about that during the time. I think this is a formulation that I’ve come to as I look back from the Trump Teens. Now we’re in this era of decay and reversion and corruption, when in the '90s, I think people were rollicking. This was the largest peacetime expansion in the economy in the history of our country. And coming after the boom-boom Reagan years, to go into the go-go Clinton years...that’s how I’ve come to look at it. Walter Isaacson said something to the effect of, “It was the era between the fall of the Berlin wall and the fall of the twin towers where nothing was troubling us.” Yes, we had the AIDs crisis, we still had wars in the Balkans and Somalia, but pretty much, these were golden years.

Was there one inciting incident or moment that made you go, “Oh, I need to write this book,” or had it been percolating for awhile?

It had been percolating. My son was playing a lot of late-night multiplayer games on the Internet, and was engaging this new thing called the World Wide Web, which started in ‘92, ‘93, ‘94. His twin sister was doing 100 sit-ups a day to try to get washboard abs like Britney Spears and threatening to get a belly ring. I was sort of thinking during the ‘90s that there’s this acceleration of sexual stimuli and cultural forces that really weren’t in play when I was their age. And this erotic overlay on life was maybe not a healthy thing. They were maybe not ready for so much of this inundation.

Then I went out to a dinner with a friend of mine, and he told me about the backstory of the discovery of Viagra. This was ten years later, in 2007. [According to him], there was this side effect to this heart drug they were testing, and the patients didn’t want to give the pills back. So that, plus what my family was going through, plus what the culture was going through, plus what I was going through...I was at Life magazine in 1998, where I’d been for 19 years, and that was sort of the mainstream, middle america, apple pie magazine. And I moved to Vanity Fair, and I stayed there for 19 years. Vanity Fair was cosmopolitan, sophisticated, saucy, sexual, probing, investigating, personality-driven, idea-driven. I think that’s what the culture was doing, too, [it] was making this shift from the mainstream to a more culturally-attuned and questioning world, so that by the end of the ‘90s, as I was at a new job at a new place, I too was understanding that the counterculture had become the culture.

Sex permeates everything, and you really get at this thing from what seems like every conceivable angle. How did you navigate that, particularly in terms of what was germane and what wasn’t?

You have to cut a lot. There are whole chapters that I wrote that don’t appear in the book. I did a chapter on the two most downloaded women on the Internet...

Who are they?

A woman named Danni Ashe. She was a soft porn star who had a huge following and who was a huge entrepreneur, made lots of money. Versus this woman named Cindy Margolis, who was a pinup swimsuit model, and, like Danni, also had her own online entity. The Guinness Book of World Records put both of them as the most downloaded woman on the Internet. [Ed. Note: To clarify, Margolis held the title in 1999, and was overtaken in 2000 by Danni Ashe.]

I did a whole chapter on Madonna’s sex book [Sex]. I did a whole section on the history of sexuality from 4 million years ago up until 1990. I had a number of sections that just didn’t make it and I think that’s how I organized it. I had a great editor in Sean Desmond...and he helped me carve out pieces and suggested what to cut. And he came up with the idea of the Clinton through line. I had aggregated a lot of the Clinton chapters together. And he said no, let’s do a Clinton chapter here [and there], and sort of weave it through the book, which I thought was really smart.

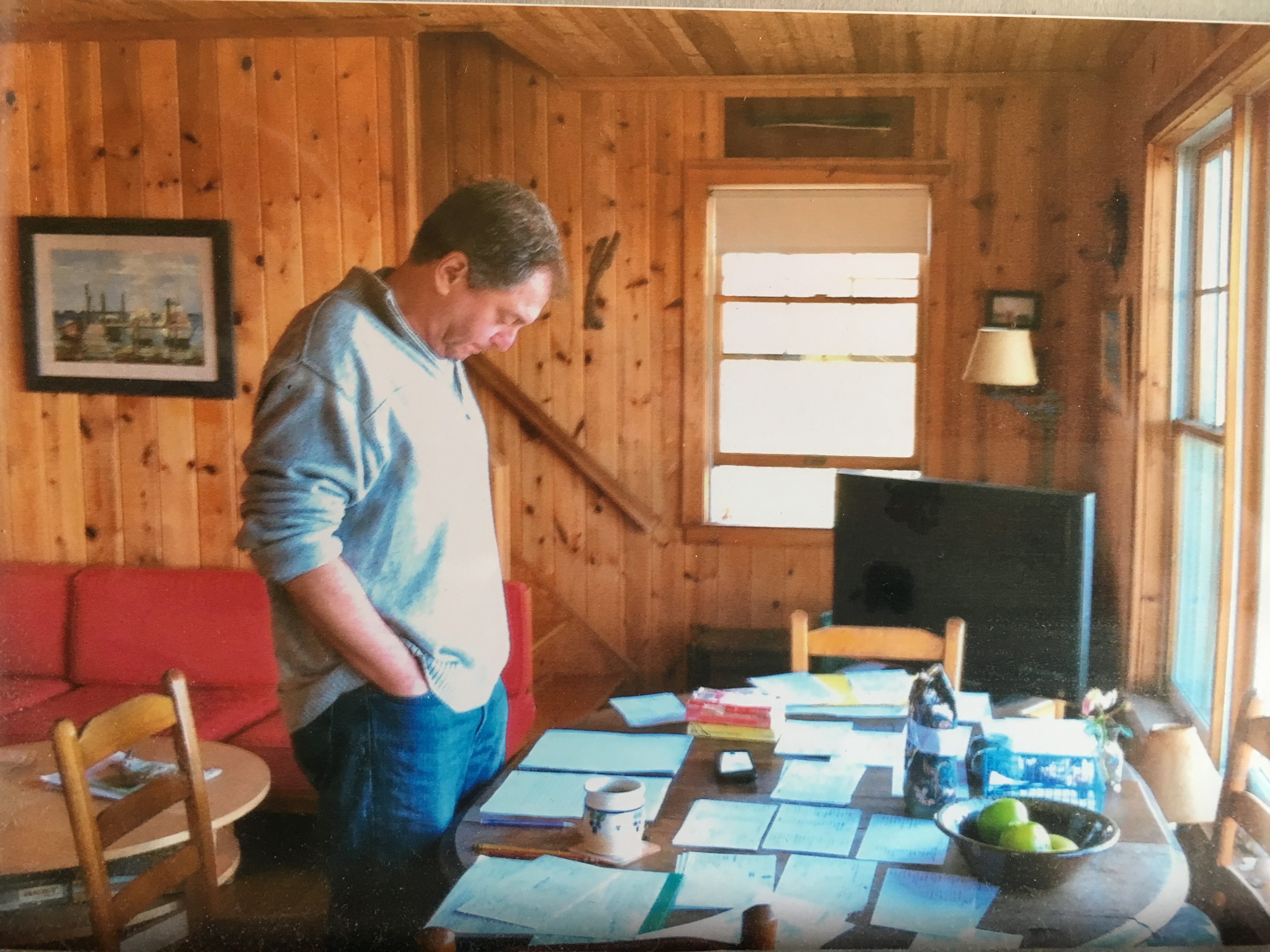

But how do you do it? I had a bunch of file cards all over my room, the floor, boxes...my wife can attest I have some twenty five boxes and files. I spent three or four years interviewing and reading and three years writing. So it was a long process. You overwrite, cut...I wrote one ending of the book where Hillary Clinton was named president of the United States. That didn’t go so well.

I imagine you had to do some rewriting or additions. But in some ways it seems like Trump is a more natural terminus.

You’re totally right. The only silver lining of Trump being president is that the book had an ending that’s so illogical it’s logical.

What was it like talking to some of these people, who were icons (or iconoclasts) in the ‘90s, 20 or so years removed?

They were really generous with their time. In the case of Monica Lewinsky we became quite friendly, our families are close. People like [famous madam] Heidi Fleiss were just terrific in opening up their lives. We were meeting in her hacienda with 20 macaws. Twice I sat down with Anita Hill who was really a pioneer I think, unwittingly so, in terms of sexual harassment in the workplace. I was extremely impressed by her. And same goes for Jesse Jackson, who I met in Washington. He really impressed me when we talked about the Million Man March.

Reading the chapter about Orgasmic Meditation, and also your article in Publisher’s Weekly, felt very Gay Talese-like. Were there any anecdotes or experiences like that that didn’t make it in the book?

I spent awhile in Vegas with this woman named Fawnia Mondey. She was the first person to do instructional pole dance videos. It really does show you just how strange the culture has become, that the aerobics and moves for stripping really became a way to get healthy and fit. And the disconnect in that...I just can’t get my mind around it. We had a great time, but it didn’t seem after all about the ‘90s. So I cut that whole section. There was no way I had the mojo or wherewithal to disrobe in front of the women. But they were great.

I was particularly struck by the chapter about men, who were renegotiating their identity and role in society in the ‘90s. It seems to me that men, particularly a vocal minority of straight white men, are even more adrift than they were back then, and it’s manifesting itself in some pretty horrible ways. Is the American male more or less lost than he was in the ‘90s?

I think Trump’s base epitomizes this underclass or working class white American male feeling. That his job’s been outsourced by foreign companies, his own home has been usurped by women and his quote-unquote “rightful place” in the patriarchy has been threatened. [This is] also true of people of color, who, for no fault of their own, have seen society rigged against them. Jobs have been going overseas, drugs have been coming into the communities, there’s been breakdowns in the family and a lot of that’s due to economic factors, not personal factors. So you have men all across the board feeling as if all these advances that many men embraced for women’s rights...disadvantaged them unnecessarily. I think that [feeling] was very prominent in the ‘80s and ‘90s. It was much less so in the 2000s and early-2010s, where it seems like there’s been much more of a balance.

But beneath all of that has been this minority of angry men who have responded in an exaggerated fashion. David Frum makes an observation [in 1992] that I quote in the book, in which he says that the mainstream Republicans, in trying to take on the voice of the far right, ended up becoming like tourists in France, who exaggerate the accents of the people they’re trying to communicate with. So basically the Republican party was hijacked. You had this rightward shift that we still have to this day. And it’s really from a minority of the party, and a minority in the country, who seem to be driving things. And it’s a lot of men trying to protect a smaller and smaller turf. What do you think?

I agree. Watching the stuff going on it feels like the racism, sexism, xenophobia, etc. from the alt-right are all wrapped up in this defense of traditional maleness.

Yeah, the traditional sense of masculinity becomes a caricature, because masculinity is a much broader tent.

It’s kind of manifesting itself in these other things.

And putting emphasis on the wrong things, [those] that have gotten us into this hole in the first place. So there’s some sense that they’re digging themselves deeper.

I was trying to think of what the most defining sexual moment of the 2010s was. And I actually thought of the Caitlyn Jenner Vanity Fair cover, and her transition. There’s kind of been this reconstitution of what a person’s sex is, as something fluid versus binary. And that, to this small section of men, must be threatening.

I don’t know if that’s threatening as much as it’s foreign, and because it’s so foreign it’s threatening. Your generation looks at sexuality as a spectrum, as fluid, to use the word you used. There used to be a brute politics around defining your sexuality and taking a stand and saying, “Wait, I am gay.” You had to take sides almost in a political way during the AIDs crisis and the era of outing, during a period when marriage equality was forming. You had to define yourself: Are you a feminist or not a feminist? I think people now are as concerned about xenophobia, racism, LGBT violence and economic inequity as they are about issues that are more narrowly defined about their sexuality and orientation.

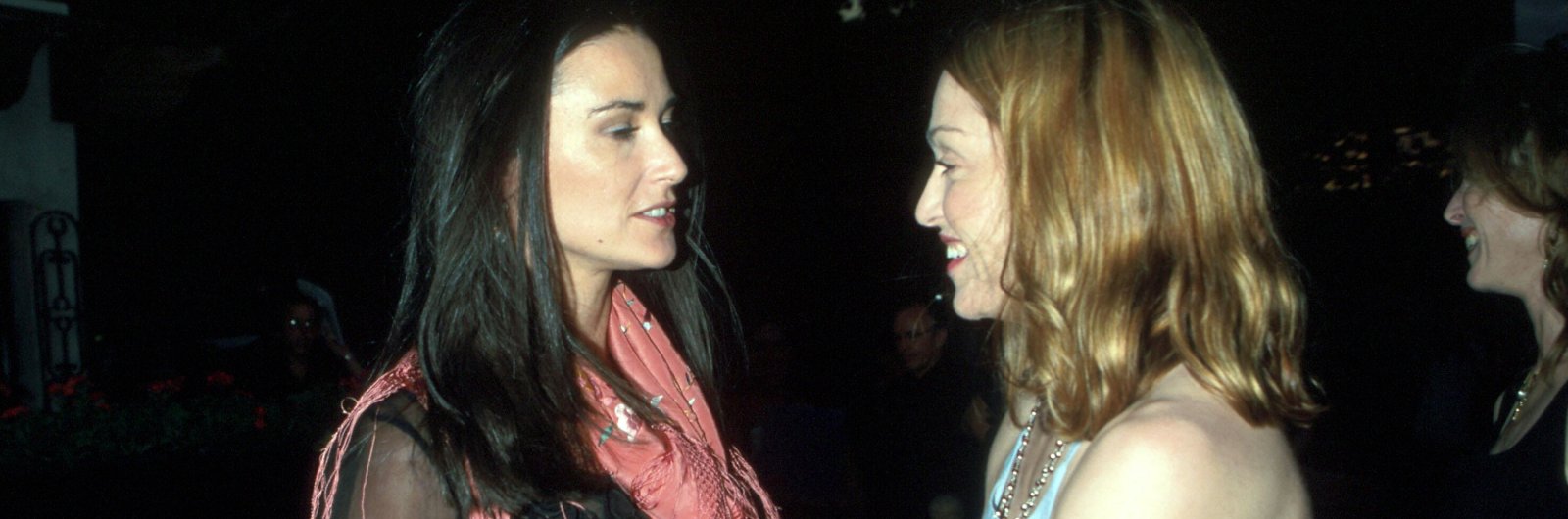

You describe Michael Douglas as the prototypical '90s male. (Male audiences, as you write, “having had their fill of '80s action heroes, were open to watching an elevated version of themselves on the screen: a ruggedly handsome, fifty-something man who had trouble keeping up with advances in women’s rights, keeping his own commitments, and keeping it in his pants.”) If you had to choose, who would you say is the prototypical '90s female?

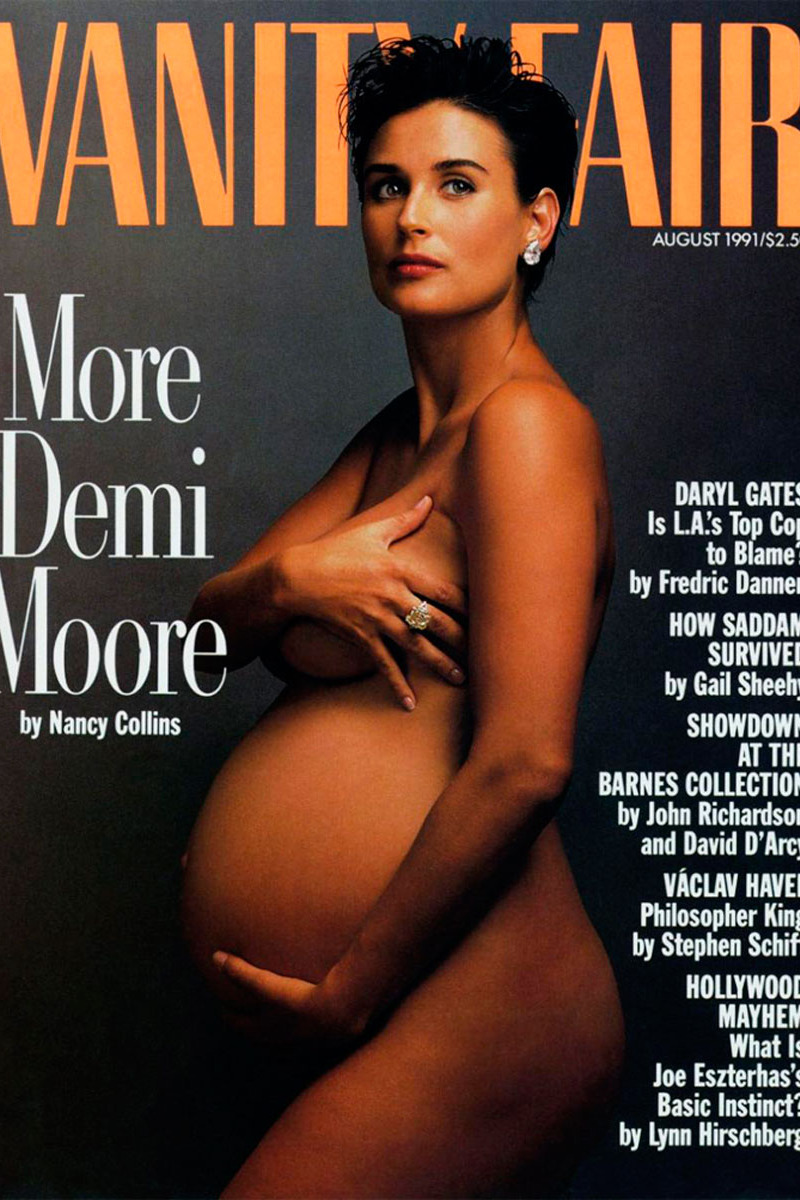

No woman influenced the era more powerfully than Madonna. Her name came up again and again as a role model among the women I interviewed for the book. And to answer your question in parallel: if Michael Douglas had a cinematic equivalent in the ‘90s (in terms of challenging sex roles on the screen) it was, hands down, Demi Moore.

In retrospect, who was the most overlooked sex symbol of the '90s?

The ubiquity of the Rabbit Vibrator. So-called "marital aids" such as dildos and vibrators, in earlier times, were not mentioned in polite company. Now women, couples and TV personalities were discussing the wonders of a new generation of magic wands.

Given your background as Life magazine's former director of photography, if you could pick only a few photographs to define the Naughty Nineties, which ones would you choose?

Benetton's colorized version of David Kirby and his family as David was dying from AIDs. Demi Moore, pregnant, on the cover of Vanity Fair. The Janet Jackson and Britney Spears covers of Rolling Stone. And Jeff Koons kinky studies of he and his then-wife Ilona Staller in flagrante.

I was surprised to learn that contemporary culture only awakened to the "sexualized bottom" with Experience Unlimited's "Da Butt." This may come off as a stupid young person question, but were people really just not into butts before 1988?

Many body parts seem to have an appeal that goes in cycles. Da Butt again cracked into the zeitgeist in the '80s and '90s, big time.

This conversation has been edited for clarity.