In the early aughts, conditions were ripe for prank television. Sandwiched between the dwindling grunge era of the '90s and peak reality TV, prank shows were the perfect bridge for two types of beloved chaos. Some shows from the genre have remained active in our lexicon (“You just got Punk’d!”), while others have faded to whatever mental storage room we’re hiding chunky highlights and asymmetrical skirts in. But the hosts, from Punk’d to Boiling Points, all possessed the same boyish (never girlish, might I emphasize) rascal energy that would get you into trouble in 7th grade and onto a TV show in 2003. And as someone who was in 7th grade that year, I was hooked on them.

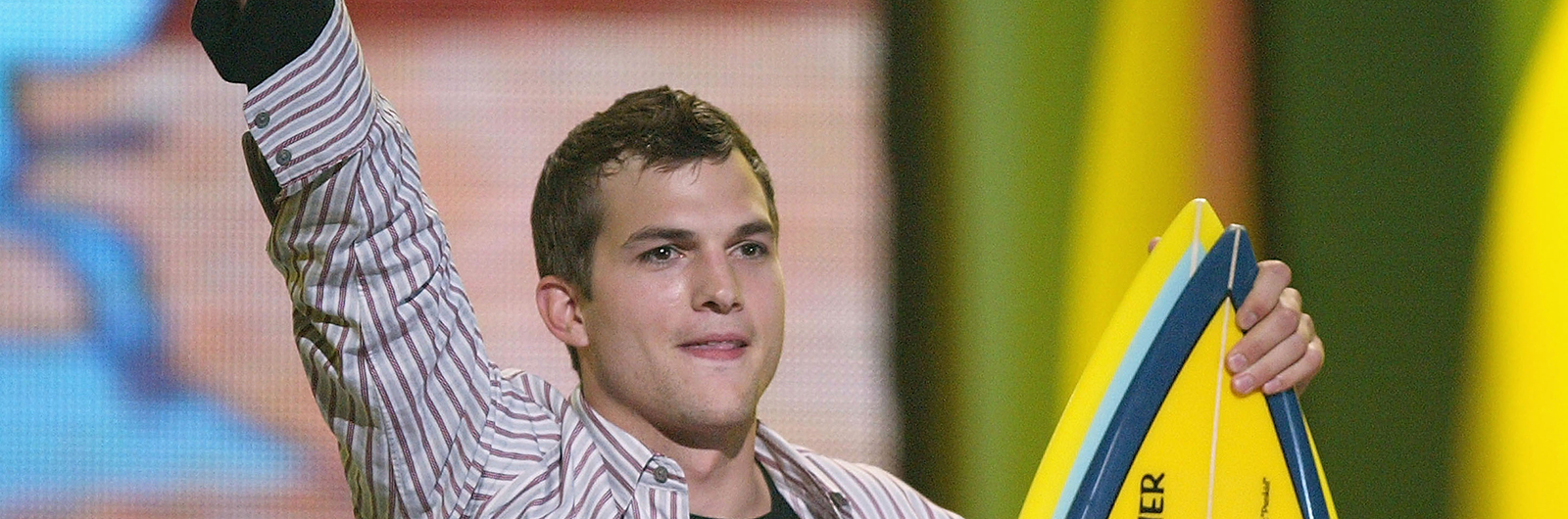

Unfortunately (or not), the tweens of today won't be: prank TV has all but disappeared. The original Punk’d aired from 2003- 2007. When Ashton Kutcher went off the air, so did Comedy Central's classic Crank Yankers and The WB's less classic Jamie Kennedy Experiment. Candid Camera, the ur-prank show (and reality show, in some respects), ended its 54-year run in 2004, and Jackass ended after three seasons in 2002. Boiling Points was on MTV from just 2004 to 2005. Currently, TruTV has Impractical Jokers, a fine program, but aside from that show, the pranking landscape is barren. What happened to these merry pranksters? Wherefore art thou, Johnny Knoxville of the Trump era?

One answer is that they haven't disappeared, they've just migrated to a different platform. Many of today's most infamous pranksters are setting up shop on YouTube. Logan and Jake Paul, Joey Salad, Improv Everywhere and countless less recognizable (though heavily subscribed to) channels are still churning out enough content to make any parent fear for their child's mental/cultural health and well-being. The platform launched in 2005 and grew rapidly in 2006, right around the time we saw all of these pranking shows go off air. It makes sense, too. It’s a genre that in its purest form is simply the result of tweens with too much time on their hands and a desire to rebel. Pranks don’t need an elaborate production budget to work (although, as with Punk'd, it can make them much grander); the DIY productions that populated the early years of YouTube were perfect for hidden camera mischief and unsuspecting prank victims. All of a sudden, Ashton Kutcher’s pranks were going up against any entrepreneurial kid with a smartphone and high-speed internet access. And those pranks were just as entertaining, at least to a young audience spending more and more time online.

Another notion to consider: would these high profile pranks sit well in our current climate? Would we even find them funny? Both then and now, these kinds of publicized pranks can go beyond entertaining levels of discomfort. Just this past winter, Logan Paul caught serious flack for a blatantly insensitive prank in Japan’s “suicide forest.” The producers behind Punk’d found themselves on the wrong side of a lawsuit in 2002, when they locked a couple in a room with “dead” body at a Hard Rock Hotel in Las Vegas. Both parties apologized for crossing the line, but the former incident reaped considerably more public repercussions, while the incident with Punk’d happened at the beginning of the show, and clearly did not hinder its future success. Our constant and ubiquitous online-ness, and YouTube's natural inclination towards virility, makes incidences like this loom much larger in the public consciousness than they might’ve in 2002. I don't think we’re more sensitive than we were back in the pranking heyday, but we are more aware, and with the incessant chatter on Twitter, people are bound to get more outraged by stuff—especially when such outrage is merited. (When Punk’d was filming it’s Hard Rock Hotel prank, the show had an entirely different name: Harassment. Just imagine how poorly that would've aged in today’s #metoo era.)

Ultimately, prank shows prey primarily on our desire to see people get bullied or tricked—a particularly unpalatable sensation in a volatile moment where our president is both bully and trickster. There's also the reality that I'm not, fortunately, in middle school any longer. These new pranksters aren't protected by the golden halo of nostalgia that the ones from my past do. Halo or not, the heyday is over. Maybe it's for the best.