The most incredible aspect of Westworld is not the impossibly lifelike AI hosts, gallivanting around drinking, eating, flirting, glitching or fucking. Nor is it the godly infrastructural might of Delos, Inc. It’s not Thandie Newton’s Maeve, or Evan Rachel Wood’s Delores, both of whom have awakened from their slumber-simulations, Matrix-like, and used their wits, brawn, charm and Lee Sizemore’s penis to accomplish their real-world goals. Hell, I’m even willing to overlook how Tessa Thompson’s Charlotte Hale managed to nab herself a seat on Delos’s board, despite being, like, what, 27? Because of all the unbelievable aspects of Westworld, the most unbelievable is still just 67-year-old Ed Harris’s William, knife-fighting, gun-slinging, horse-riding, whiskey-drinking and generally cowboy-ing through ghost towns like a young John Wayne, rendered in resplendent high-def.

Have you looked at Ed Harris in Westworld lately? Seen the sun-hardened skin stretched taut and leathery across his face? Observed his belabored gait? Heard his anguished grunts and sighs as he throws back another shot of warm whiskey? Winced as he tended to his own wounds without so much as a grimace? Shielded your eyes as he took cover behind a well, then rolled under a human shield, then took out a gunman and slit another gunman’s throat? Wondered how his AARP-qualifying muscles could possibly hold up against a robot trying to stab him through the head? Considered the strong thighs and fortified midsection necessary to ride that black horse all day long? Imagined how he’s holding up despite dying from cancer? (Sorry, different Ed Harris.)

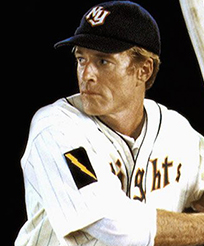

Ed Harris, as the “man in black,” aka, Old William, aka, some other character in a different timeline we haven’t discovered yet, looks tired, world-weary, defeated. After years spent mastering Westworld, he’s dead-set, in season two, on winning a game with “real stakes”—even if it costs him his life. In a theme park devoid of other humans—following that inordinately macabre gala in season one—William has become the only living boy in Westworld.

This would be a lonely condition, were it not for the fact that William doesn’t seem to think much of humanity in the first place. He’s content to saddle up with his robot compadre, Lawrence, and scour the frontier for days, weeks, months, if it means winning Ford’s little game (which, let’s face it, already seems unwinnable). While the remaining humans arm themselves with modern weaponry, or desperately submit themselves to the whims of more powerful hosts, or simply luck out by being a Hemsworth, Harris’s William is still out there in the sun, wearing all black, sans body armor, with a low-tech revolver and a horse. His bravery and will and brute force is decidedly human; in Harris’s hands, William’s physical pain feels real—an oft deceptive term in Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy’s postmodern funhouse.

One of the accomplishments of Westworld, and any good sci-fi, is that it tricks you into taking extraordinary technological advancements as quotidian byproducts of everyday life. Thus, after the initial shock, the intricate code, those crazy 3D printers, the vague voice commands, the dangerously slim iPad-like devices, appear commonplace. No matter how successful the show is in getting its audience to invest in the emotional and narrative arcs of its hosts—and it is pretty successful—the trials and tribulations of Delores, Maeve, Bernard and Cowboy James Marsden pale in comparison to those of real humans (even the shitty ones). This isn’t because they are less human, per se—although, in several fundamental ways, they are. They don’t age. They don’t appear to exhibit physical human needs (although, apparently, they can poop). And we’ve been conditioned by the show itself to believe that their deaths are never permanent; all they require is someone with a rudimentary command of that touchscreen-y thing to wake them back up and whip them into shape. They are engaged—to borrow from The Avengers, both literally and thematically—in an Infinity War.

Therefore, the stakes will never be as real for a host as it is for a William. Which makes Ed Harris’s mere mortal action hero moves that much more fantastical by comparison. There is nothing newly incredible about the technology in Westworld, or the feats of its hosts (at least not yet). But there is something wildly hard to believe, in a good way, about very not-young William falling down, dusting himself off and getting right back up, again.