Kodachrome, which goes up on Netflix Friday, is one of those movies that knows exactly what it’s about and isn’t afraid to show it. It lays its themes bare, and then, if you still can’t see them, does you the favor of pointing them out: “Look over here! A motif!” It’s almost embarrassingly obvious. If you’re even a casual fan of movies, it’s likely you’ll be able to foresee its entire arc 15 or 20 minutes in. And yet it’s a pleasurable experience, even moving, buoyed by solid performances from Ed Harris and Jason Sudeikis, and a compelling script from the novelist, Jonathan Tropper.

Those familiar with Tropper’s work will feel right at home Kodachrome. He is, in some ways, a more middlebrow Jonathan Franzen, which I don’t mean as an insult—his books are breezy and entertaining family and relationship dramas, heavy on thirtysomething white male and/or artistic ennui, that tend to hinge on the kind of readymade cinematic events that force characters to reconnect with old flames or estranged kin and confront their past: a family Shiva, emergency heart surgery, a father’s stroke, an intervention. It’s no wonder three of his first four books were optioned within a week of publication; This Is Where I Leave You, the only adaption to make it to the big screen, was a mawkish rigmarole, with an unfortunately laughable performance from Tina Fey. (Tropper, it's worth noting, also co-created the Cinemax series, Banshee.)

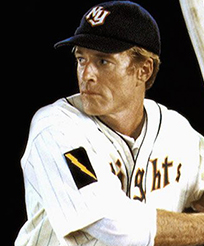

Working this time with director Mark Raso, Kodachrome—based on this article, not a novel—is thankfully much more coherent. It tells the story of a boutique record executive, Matt Ryder (Sudeikis), who is roped into taking a road trip with his estranged, dying father, Ben (Harris)—a world-renowned photographer—and his father’s personal assistant/nurse, Zoe (Elizabeth Olsen), to develop four rolls of “kodachrome” film at the country’s last processing outpost, in Parsons, Kansas. Despite his hatred for his father—a serial philanderer who left him with his aunt and uncle following his mother’s death—Matt agrees to go on the trip, if only because Ben’s manager has secured him a meeting with a band called the Spare Sevens, whom he needs to sign to save his job.

Though Matt is surly towards his father, with Sudeikis’s familiar brand of smartass-ness, he eventually warms up to Zoe, who, like Matt, has gone through a messy divorce. It’s clear the film is pushing the two together from the moment she walks on screen, but, in spite of itself, they manage to make the will-they-won’t-they interesting. A particular gambit, which involves Matt guessing the music Zoe used to listen to, is pretty emblematic of the film as a whole: irresistibly entertaining yet totally obvious. It’s also revealing in a different way: neither Matt nor Ben has any real interest in Zoe’s backstory or feelings. Mostly, she is a pawn set between father and son, hanging around explicitly for the redemption of the movie’s male protagonists. In the beginning, she’s a paid companion for Ben; by the end, she’s a narrative device for Matt. Still, Sudeikis and Olsen’s chemistry is such that you can’t help but want to see them end up together.

Despite all this, the film is preoccupied with bigger issues—namely, the things we leave behind, and the things we can’t let go of.

“Years from now, there won’t be any pictures to find,” Ben explains to Matt, when Matt jokes that they all could’ve saved a lot of time—nay, an entire movie!—had he shot on digital. “What’s the point of an artifact if you never see it with your own eyes?” Matt retorts. To which Ben inquires, rhetorically: “We still talking about film?”

Alas, it was Ben’s job to see, but Ben never saw Matt—or so Matt thinks. And while his father was busy creating artifacts out of other people’s lives, he ultimately failed to cherish the greatest, living artifact right in front of him. The movie’s engagement with this concept cuts both ways; while it celebrates the physical commemoration of a moment in time, the tangibility of these artifacts also seems to represent an inability to move on from the past, a problem both Matt, with his grudge against his father, and Zoe, with her marital woes, eventually need to overcome if they’re to live happily ever after. (That Matt himself is tethered to those totems—as an older A&R guy, he’s having trouble adjusting to the digital landscape—only belabors the point.)

Of course, Ben’s photos are literally the last on earth to be developed on kodachrome film, a flourish so hyperbolically on-the-nose as to become allegorical. I won’t spoil the twist at the end, but suffice it to say, you’ll probably see it coming—which doesn’t necessarily make it less moving. In fact, its utter predictability ends up engendering some juicy dramatic irony, if unintentionally.

Viewed one way, Kodachrome is a love letter to the analog and the tactile; viewed another, it uses the uneasy, yet inevitable transition to digital as a metaphor for its characters’ need to break from the past. Sure, it could be both; it probably is. But I’m partial to the latter view. Of all its blatant symbolism—Kodak film, the record industry, Ed Harris flippantly tossing a fancy GPS out of the car in favor of a roadmap—perhaps the most blatant is the one the movie embodies itself: it’s a film about film shot on film streaming via Netflix on a computer near you.