In 2017, the most important politician was not a politician, but a reality TV star; the most important athlete was not an athlete, but an activist; and one of the most important movies was not a movie, per se, but a complex piece of meta-art.

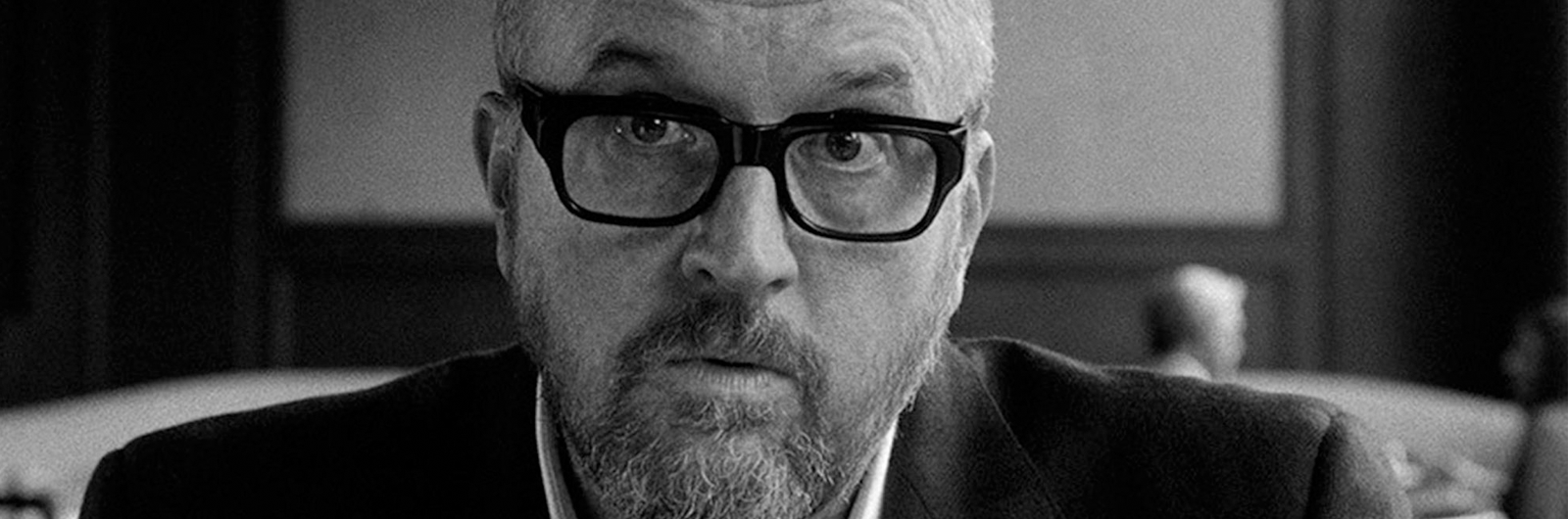

The movie (or non-movie) of which I speak is Louis C.K.’s I Love You, Daddy, whose release was infamously halted by The Orchard, following several allegations of sexual harassment against the director—which he later admitted to—that involved C.K. masturbating in front of or on the phone with women, without their consent. The rumors had been out there for years, and, in retrospect, C.K.’s myriad bits about masturbation in his stand-up have been viewed as both a confession of his private shame and a shameless flaunting of it. These two acts, though ostensibly opposed, are not mutually exclusive.

I Love You, Daddy stars C.K. as a successful TV writer whose 17-year-old daughter, China, (Chloe Grace Moretz) becomes, to his chagrin, romantically entangled with a filmmaker more than 50 years her senior (John Malkovich). Despite being an alleged child predator, he’s one of the TV writer’s heroes. As many have pointed out, the relationship is a blatant reference to Woody Allen, an exalted filmmaker who was famously accused of molesting Dylan Farrow when she was just a child, and who had an affair with (and later married) the adopted daughter of his then-wife Mia Farrow, Soon-Yi Previn, when she was just 21-years-old. “Like Manhattan,” critic K. Austin Collins writes for The Ringer, “I Love You, Daddy is a New York tale filmed in black and white, rich with monied neuroticism and other stylistic riffs on the Allen Extended Universe.”

Jacob Knight, a critic for Birth.Movies.Death, notes that China’s relationship with the older filmmaker “becomes a metatextual representation of C.K.’s fears regarding how he’s viewed, particularly in relation to one artist he reveres. Do people really look at me like Woody Allen because of these ‘rumors’?” Collins argues that the movie wants us to be “both grossed out and intrigued by the connection”; in the aftermath of his sexual harassment revelation, “we’ve only given [C.K.] what, according to the movie, he was secretly demanding of us: that we acknowledge his sins. That we participate in his shame. Once again, he’s wielded his art as a means of confession. And once again—even without the release of his movie—he has recruited us to bear witness.”

I have not seen I Love You, Daddy—nor will I be able to, unless C.K., who is reportedly purchasing the rights back from The Orchard, decides to release it on his own (or I can find a pirated version). Even then, the movie will be dwarfed by the reason it wasn’t released; as these critics, and others, have showed, it’s simply not possible to watch or think about the movie without also considering the transgressions of its creator. Its meaning is derived almost entirely from the moment in which it resides. For the general viewing public, with only a trailer and a few reviews at our disposal, the film is less a film than a piece of post-modern meta-art playing out within and beyond itself, in both fiction and reality. Even its title smacks of extra-textual significance: I Love You, Daddy, in retrospect, sounds like Hollywood’s wistful farewell to the patriarchy of old. Amidst the #MeToo moment, the controversy circling the movie subsumed the movie itself; its artist has not only overshadowed his art, but has fallen prey, in real life, to some of the very answers—regarding the perception of his morality, as it relates to Allen’s—that his film was so desperate to provoke.

It’s interesting, here, to compare I Love You, Daddy with another important movie from this year, the documentary Jim & Andy: The Great Beyond, which also mines the dichotomy between art and artist, albeit in a different way.

The film weaves backstage footage of Jim Carrey, who went full method as comedian/provocateur Andy Kaufman for Milos Forman’s biopic, Man on the Moon, with one long, meandering interview with Carrey—about his career, his fame and his place in the cosmos. It is a brilliant exercise in restraint, a focused and fascinating case study of two similarly singular performers. Kaufman took a performance artist’s approach to stand-up comedy. In one prolonged bit, he starred as the antagonist of an inter-gender wrestling league; in another, he disappeared, over the years, into the character of a ribald nightclub singer, Tony Clifton—refusing to acknowledge, even privately, that he was merely playing a part. Per Man on the Moon, it was apparent from a young age that Kaufman never knew, or wanted to know, where the joke ended and life began.

Carrey, on the other hand, after skyrocketing into global stardom, lost sight of himself in the blur of the larger-than-life characters he portrayed on-screen. His movies at the time, as he explains in the documentary, had a kismet way of mirroring his life.

“At some point, when you create yourself to make it, you’re going to have to let that creation go and take a chance on being loved or hated for who you really are,” Carrey says. “Or you’re going to have to kill who you really are, and fall into your grave grasping onto a character who you never really were.” As he and the filmmakers very well know, this may as well be the plot summary for The Mask.

The Truman Show also reflected his existence—as a man “in a bubble,” trying to escape the part he was sentenced to play. Even Michel Gondry’s masterpiece, Eternal Sunshine of a Spotless Mind, wherein people could have their memories of loved ones erased after heartbreak, seemed trained on Carrey’s demons: “I felt like I had been erased,” he recalls. His “creation” had stamped him out. By inhabiting Kaufman for Man on the Moon, going so far as to talk to his director and Kaufman’s real family members completely in character, Carrey both avoided having to reckon with his own identity and engulfed himself in an entirely new one. It’s unclear, from the documentary and Carrey’s career in the aughts, whether he’s come out the other side fully intact.

While C.K.’s personal misconduct swallowed his work whole, the opposite is true of Carrey—the work swallowed him. Both reflect a paranoiac year where the line between art and artist, art and politics, and politics and everything else has bled together to a degree the likes of which we’ve never seen; where the minute chronicling of the presidency has become a nightmarish 24-hour reality TV show. I Love You, Daddy, in particular, manages to stay relevant despite its absence—and is perhaps more relevant because of it. In this way, it serves as an apt encapsulation of a year in which our chief executive’s tweets stand in for actual policy, and our most important athlete, in the most American of sports, in the most American of positions, hasn’t played a single down. Indeed, Donald Trump and a Republican congress have passed hardly any significant legislation—the tax bill pending—and yet this has been perhaps the most profound year for politics in the history of the republic. Colin Kaepernick has not played football since 2016, and yet he just won Sports Illustrated’s Muhammad Ali Legacy Award. Harvey Weinstein has been banished from the movie business, and yet the first sentence of any major story about Hollywood in 2017 will inevitably bear his name. In all three instances, the cult of personality has eclipsed the policy, or stats, or movies these people would’ve been scrutinized, celebrated or criticized for in the past. And with the ubiquity of social media, with the threshold for the highest office in the land lowered to that of an ex-reality TV buffoon, how could it not? When politics become personal, and the personal becomes public, as both did in an unprecedented way this year, they do so at the expense of what the culture used to focus on: the art over the artist, the athlete’s performance over the athlete’s character and, to a lesser extent, the politics over the politician.

Mostly, this is a good thing. The #MeToo movement still faces significant obstacles—it’s still iffy, particularly in the wake of the recent allegation against New Yorker writer Ryan Lizza, where due process comes into play—but it has, for circles with a sense of shame (i.e. not congressional Republicans), succeeded in ousting men who have flagrantly abused their power. Kaepernick, and the protests he set off across the NFL, have certainly brought increased awareness to police shootings. Trump, however, is a different animal: a blowhard who continues to bait-and-switch the media with shallow personal politics—tweetstorms, vendettas, childish nicknames—to distract from his complete ambivalence towards and utter ineptitude in actually governing.

It can be easy (this essay being a prime example), to get swept up in the personal politics of our public figures—to let the bad news about artists like Louis C.K. and Kevin Spacey carry the day; to scroll through Twitter for tweets about Trump’s tweets, rather than get in the weeds of legitimate issues; to feel as if art for art’s sake is less than, or irrelevant, in these trying times.

But lest we forget, this was a year, at least with regards to the movies, whose most political film—Get Out—was a $4.5 million horror movie directed by a first-time black director; whose highest-grossing adult comedy—Girls Trip—starred four black women, one of cinema’s most underrepresented demographics; whose best superhero movie—Wonder Woman—and most well-reviewed film—Lady Bird—featured female protagonists, and were directed by females, too. So while I Love You, Daddy is certainly emblematic of the way in which politics has, for better or worse, flooded every sphere of private and public life, the movies themselves have nonetheless spoken with greater potency about the future of the medium—and the society within which I hope they’ll live.